Welcome to the second edition of this small newsletter. It includes features on the recent counterfeiting of the South African five rand coin and a shortened version of my "Numismatist" article on the counterfeiting of the currency sovereign. The last six months have seen a lot of news on the counterfeiting of circulating coins. Hopefully this newsletter will give you at least a taster of all this activity.

There is less news from collector coin counterfeiting. I wish that this meant that there is less of this type of counterfeiting taking place. However this world has always been a very opaque one where many participants prefer to keep the problem hidden. This has been made worse by the decision of the American Numismatic Association, ANA, to stop publishing the "Counterfeit Coin Bulletin". Since April 2000, the ANA had published this jointly with the International Association of Professional Numismatists, IAPN. Previously the International Bureau for the Suppression of Counterfeit Coins, IBSCC, a subsidiary of the IAPN, had published the "Bulletin on Counterfeits" from the 1970s. To date the IAPN has not announced if they have any plans for a replacement.

The ANA is the largest membership organisation in the coin world. The IAPN represent some of the most respected and financially sound coin dealers in the world. It is disappointing that between them they could not continue to support this vital service to coin collectors. It means that the coin collector is now at the mercy of unsubstantiated rumours and the self-appointed experts of the internet world.

I have posted a cumulative index of the "Counterfeit Coin Bulletin" on my Coin Information website. From this it can be seen that the Bulletin's coverage was very biased towards USA milled coins, 4 Greek coin reports, 3 Roman coin reports, 53 USA milled coin reports. This was arguably a justifiable corrective to a similar if less blatant European bias in the "Bulletin on Counterfeits". Provided copyright law is respected I will supply a summary of an individual coin report to anybody who requires to check a particular coin.

EDITORIAL

NEWS

Euro counterfeiting 2003

Second type of Japanese 500-yen counterfeit coin found

Counterfeiting snippets from around the world

FEATURE

The counterfeiting of the South African five rand coin

FEATURE

The counterfeiting of the British sovereign in the second half of the twentieth century

Euro counterfeiting 2003

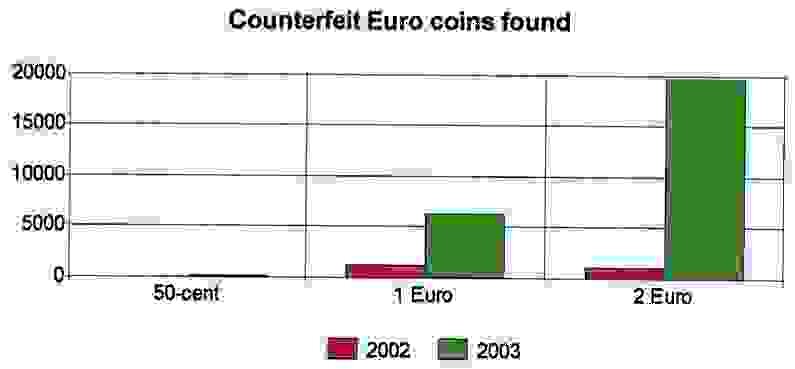

The announced that a total of 26,339 counterfeit coins were withdrawn from circulation by the National Central Banks in 2003. This was a 1,120% increase over the number withdrawn in 2002. 13,186 counterfeit coin, just over 50% of the total, were withdrawn by the Deutsche Bundesbank.

The European Commission stated that, "the quality of the counterfeit coins has globally improved, especially for the 2-euro". They opinioned, as in 2003, that the counterfeit coins, "should generally be rejected by properly adjusted vending and other coin-operated machines". At the time of writing the European Technical and Scientific Centre, ETSC, had not published its annual report for 2003, so we are lacking more detail on the counterfeit coin types. Anecdotal evidence on a small number of counterfeits examined by coin collectors show they are not magnetic, that is they do not contain a nickel core, and they have poor quality edges.

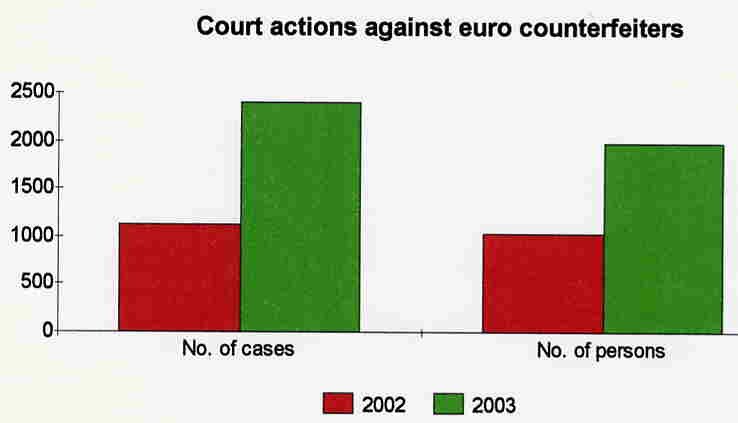

Europol reported a 112% increase in the number of euro counterfeit cases, both notes and coins, reported to it during 2003. Although Europol state that two "mint shops" were dismantled in 2003 they had previously reported, see Counterfeit Coin Newsletter No.1, that three illegal mints were dismantled in the first six months of 2003. The European Commission confirmed this. Two of these illegal mints were in Italy and one in Portugal.

In April 2004 Spanish news sources reported the arrest of four people and the seizure of 160,000 counterfeit 2-euro coins. Three of those arrested were Italian. Police also seized several metal presses. The counterfeit coins had Spanish, Italian and German obverse designs. Costa del Sol News reports that the illegal "mint" had been in existence since mid 2000 and that 2,000 counterfeit 500-pesata coins were also found. The report claims the equipment and materials used originated in Italy.

The Japanese 500-Yen coin, introduced in 2000

Weight: 7.0g

Diameter: 26.5mm

Alloy: nickel brass

(Cu 72%, Zn 20%, Ni 8%)

In Counterfeit Coin Newsletter No.1 the finding of the first examples of counterfeits of the new Japanese 500-yen coin was reported. A subsequent report in The Asahi Shimbun describes the discovery of bags of counterfeit 500-yen coins in a factory gutted by fire in Ipoh, Malaysia. Machinery for producing counterfeits and partially produced coins were also found. The man who rented the factory has disappeared.

The counterfeits were apparently paid as wages to three Malaysian trainees in Japan. Previous to this discovery an Indonesian flight attendant had been arrested for possession of nine counterfeit 500-yen coins in Osaka. She claimed she did not know the coins were counterfeit.

All the counterfeits mentioned above were made from the same material, nickel coated brass. This would have been determined at the Japanese National Research Institute of Police Science (N.R.I.P.S.). Counterfeit coins are examined by stereo and comparison microscope, their conductivities measured and they are analysed semi-quantitatively by X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The counterfeit coins are then classified according to their characteristics.

A report in The Japan Times describes how Tokyo Customs had found 17 counterfeit 500-yen coins in a consignment of mail sent from China. The Finance Ministry said that the counterfeit coins were made of the same material, copper and nickel as the genuine coins. They told Mainichi Shimbun that similar examples had been found on several occasions since April 2004. They all appear to have originated from the same source. These counterfeits were considered to be of a better quality compared to those mentioned earlier.

The counterfeit coins had either a 2001 or 2002 date and were slightly lighter than usual. The "500 yen" mark inside the zeros on the counterfeit when held up to the light were considered blurred and other fine details were missing. The Finance Ministry said that because of the similar material being used the counterfeit coins could be used in some vending machines. However they are quoted as saying, "We do not think that the forgery-prevention technology has been broken".

Circulation coins

In December 2003 the British Royal Mint completed a second survey of the numbers of counterfeit one pound coins in circulation. Ruth Kelly, Financial Secretary to the Treasury announced that the results found just under one percent of counterfeit coins. This was almost identical to the previous years survey. She also announced that since 1997 63 persons had been arrested in England and Wales for counterfeit coin possession and production.

The National Criminal Intelligence Service has refused to breakdown these figures for your correspondent into annual number of arrests, numbers of convictions etc. However Mr. Nigel Evans, MP, is attempting to obtaining further details. Mr.Evans is concerned that the large number of one-pound counterfeits will affect small business.

Collector coins

Some attempt to pretend that there is no significant counterfeit problem in numismatics, below are just a few quotes illustrating it is a serious problem.

"Counterfeits have plagued the numismatic hobby....for as long as there have been coin collectors", Lawrence J.Lee, former ANA Curator.

"Despite efforts..counterfeits and altered coinage..can still be easily found in the market place", Numismatic Conservation Services.

"Replicas and counterfeit copies have been produce of all known numismatic rarities", ANA.

"New methods of die production have made it possible to copy genuine coins with extreme accuracy", Wayne G.Sayles.

"It is hard to overstate the problem. The current market is over run with fakes of ancient Chinese..cash and related cast bronze objects", Scott Semans World Coins.

This situation has been made much worse with the advent of the world wide web and internet trading. The internet is full of numerous scams of which counterfeiting is only one. The warning is not just buyer beware but buyer and seller beware! One dealer sold a coin via the internet and had the coin returned as unsuitable. The only problem, the returned coin was a cast counterfeit and not the original.

John J. Ford Jr

"How the West was faked"

Dr.John M.Kleeberg, formerly American Numismatic Society (ANS) Curator of Modern Coins, and Professor T.V.Buttrey, formerly Keeper of Coins, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge University, have recently established a valuable website, titled, "How the West was faked". The website contains a long essay by Dr.Kleeberg presenting the evidence which exposes many of the "Western assay ingots" as fakes. It also includes a number of shorter essays by Professor Buttrey of undoubted scholarship but full of passionate scorn for those he considers that have "corrupted the study of Western American numismatics."

Another useful site on the same subject is the ANA site, containing the paper, "Western Precious Metal Ingots The Good, the Bad and the Ugly", by Fred N.Holabird, Robert D.Evans and David C.Fitch. This large pdf paper may take a little while to load for those without a broadband conection. For those wishing to hear from one of the men at the centre of this controversy there is a rather folksy interview with John J.Ford jr. on the Finally to show the complacent attitude of the "numismatic establishment", there is by Q.David Bowers, on the ANS site. Disturbingly the introduction to this piece states that, "This communication will conclude the discussion on this topic in any of the publications of the American Numismatic Society". In May 2004 the ANS dedicated the John J.Ford jr. Reading Room in the Harry W.Bass Library.

The current five rand, R5, coin was introduced in 1994, the first year of the new ANC government. It is an unusual coin consisting of a relatively thick pure nickel plate on a bronze substrate. The coin's design consists of an obverse of the South African coat of arms and a reverse of a black wildebeest. The edge is milled. 114 million of the R5 coins had been issued by January 2003.

Weight: 7.00g

Diameter: 26.0mm

Edge

Thickness: 1.75mm

Composition

Plate: pure nickel

Core: copper, 95.0%

zinc, 4.5%

tin, 0.5%

The Counterfeiting of the South African Five Rand Coin

The recent counterfeiting of the South African five rand coin is unusual. Normally we only get a very partial view of modern counterfeiting activity. However because of commendable openness by the South African authorities, an active press and successful police action, a fuller picture of the counterfeiting of this coin has emerged. It involves sophisticated counterfeiting technology, commendable police work, prison escapes and a glimpse at the international nature of modern crime.

The first publicity occurred on 17th January 2003 when the South African Mint issued a in response to public concern about the circulation of counterfeit five rand, R5, coins. The main concerns seemed to centre on Gauteng, the South African province containing Johannesburg and Pretoria. Historically this province was part of the Transvaal and centre of the country's mining and mineral industries. Its population of over 7.6 million is the largest of any province and it has the highest population density in the country.

Initially, as is the tradition with monetary officials the world over, both the South African Mint and the Reserve Bank attempted to minimise the issue. However by the end of January 2003, the Dispatch was claiming that, "a R5 coin is practically worthless". It claimed that taxi drivers, shopkeepers and other outlets around Johannesburg were rejecting the coin. Carte Blanche Interactive interviewed one small Johannesburg retailer who estimated one in ten R5 coins were counterfeit. FNB Retail also told them that a nationwide sample test of 2,500 coins carried out with the Reserve Bank found 2% of R5 coins were counterfeit.

Tito Mbweni, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank

During this time many shopkeepers and taxi drivers were using their own test to tell whether a R5 coin was fake. They used a magnet. They believed genuine coins were attracted to the magnet while counterfeit coins were not. The South African Mint confirmed, note 1, that the counterfeit coins consisted of a copper or copper/zinc core with a very thin nickel plate. The difference in plate thickness undoubtedly caused the difference in attraction to a magnet. This test appeared to be accurate but the South African Mint and the Reserve Bank discouraged its use. They appear to be concerned that genuine worn coins would fail the test and new counterfeits with either a thicker plate or an iron or steel core would pass the test.

The Mint and the Reserve Bank did issue about visually identifying the counterfeits. However they stated, "The only accurate method of determining if a coin is genuine or counterfeit is to conduct a chemical analysis of the coin".

As well as the initial concerns about counterfeit R5 coins in Gauteng, reports of counterfeits came later in 2003 from Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape and Kimberley in the Northern Cape.This widespread distribution of the counterfeits probably helped shape the decision announced by T.T.Mboweni, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank at the meeting of shareholders on 26th August 2003. He said that, "A decision has also been made to introduce a new R5 coin in response to the counterfeiting of such coins".

Police action catches the counterfeiters

From September 2002 the South African Police Commercial Unit were pursuing the makers and distributors of the counterfeit R5 coins. In February 2003 they made two breakthroughs in quick succession. On 4th February they arrested a married couple of German origin who had been resident in South Africa for thirty years.

Wilfred Lautenberg, Acting Managing Director(2003), South African Mint

The man, Richard Widney, was arrested at an illegal "mint" in Benrose, Johannesburg. At this "mint" were found counterfeit R5 coins as well as manufacturing equipment including electroplating plant. Two days later Business Day reported, that the South African Mint was the possible original purchaser of the coinage press found at this illegal "mint". After plea-bargaining, Widney, pleaded guilty and was convicted in March 2004, of manufacturing counterfeit R5 coins between 1999 and 2003. Widney was sentence on 24th May 2004 to three years house arrest and eight hours community service. This "leniency" (see below) was apparently due to Widney having a chronic health condition.

After examining the illegal "mint", Wilfred Lautenberg, South African Mint, was quoted as saying that the equipment could possible produce up to 20,000 coins per day. However he said this production rate was highly improbable.

The second breakthrough involved the arrest of a man of Belgian origin, and his daughter and her husband in Tarlton, West Rand on 12th February 2003. An illegal "mint" was found on their small holding containing counterfeit R5 coins and manufacturing equipment. In February 2004, again after plea-bargaining, the father, Rene Collen, pleaded guilty to possession of the oven, tools, engraving and manufacturing equipment used in the production of counterfeit R5 coins. He also admitted the issue of coins between August 2002 and February 2003. He was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

A number of people associated with one or other of these syndicates were arrested in the first part of 2003. From the reports it has not always been possible to be clear to which of the two groups they were connected. Three of these were Israelis and two escaped from custody in two separate incidents. One, Simon Kachlon alias Reuven Tovim, is wanted on an international warrant for drug trafficking in Israel.

In November 2003 the police discovered 17 tonnes of "gilded" metal in Germiston, East Rand. It is believed this metal had been imported by the "Benrose group" and was capable of making 8 million Rand worth of R5 counterfeit coins. Gilding metal is the traditional name for a low zinc copper alloy, typically 95% copper and 5% zinc.

Comparison of counterfeit(A) and genuine(B) obverse sides of the R5

The counterfeits

It has not been possible to obtain samples of the counterfeit R5 coins to produce an independent report. Reliance has been placed on the published reports, photographs and statements from the South African Mint.

The South African Mint, note 1, stated that the weight and diameter of the counterfeits were similar to the genuine coin. However they stated that the edge thickness was thinner than the genuine coin. This was considered to be due to the counterfeiters not rimming the coin blanks prior to coining.

As previously mentioned the counterfeits have been found to consist of a copper or copper/zinc core with a thin nickel plate. Some reports state that the counterfeits appear darker or duller than the genuine coins. This could be due to a number of factors including the purity of the nickel plate, the plating conditions and any polishing of the blank or the final coin. It is not clear at which stage of the manufacturing process the nickel plating took place. The South African Mint, note 1, stated that there was no evidence to suggested heat treatment after plating. This is usually carried out to improve the adhesion between the plate and the core material.

It appears all the counterfeits found are struck coins. The South African Mint, note 1, stated that they were made with a very low press force. The Mint also have confirmed that two methods were used to manufacture the counterfeit dies. Spark erosion and scanning the coin design into a computer and then cutting the design on to a die. It is believed this is the first published case of the use of computer scanning and the subsequent cutting of the counterfeiting tool under computer control. The use of the technique has been suspected previously but no confirmation published.

Close examination of the by the Reserve Bank shows a lack of fine detail. This is probably due to both the die manufacturing techniques used and the low press force used during coining. "Zooming" in on the photograph of the counterfeit it is possible to see a roughness on the vertical parts of the design elements. This roughness is usually due to the use of spark erosion produced dies and this is probably the case. However it is possible that it is due to an effect of the electroplating. Unfortunately only examining the counterfeit in hand would resolve this question.

Note 1: reply by Antonie Naude, Manager: Quality Technology, South African Mint, to a series of e-mail questions from Robert Matthews.

The counterfeiting of the British sovereign in the second half of the twentieth century

[This feature was the basis for an article I wrote, "Sovereign Fakes", which appears in the July 2004 issue of Numismatist]

In November 1954 a British Assistant Treasury Solicitor, Ralph Anderson, visited the Damascus moneychangers’ market. He found openly quoted for sale, British made, Swiss made, Italian made and Syrian made gold sovereigns. Each had a different quoted price. The genuine British made sovereigns being the most expensive and the Syrian made fakes the least. Anderson was one of the leaders of the British fight against the post-war counterfeiting of the gold sovereign. This must have shown him how far he still had to go in his battle to prevent the counterfeiting of the sovereign.

In the twentieth century there was no significant counterfeiting of the sovereign until after the Second World War. By this time the sovereign had been completely replaced in every day use in the United Kingdom by bank notes. However in many areas of the world such as Greece and the Middle East the sovereign was still in great demand.

Large scale minting of the sovereign for circulation ceased in the London Mint in 1917. The six branch mints carried on making relatively small numbers of the coin for some time after this. The Pretoria Mint in South Africa made the last branch mint coins in 1932. This drying up of supply with an unsatisfied demand led to the price of a sovereign rising much more than the price of the gold it contained. London’s Evening Standard reported in 1952 that although the nominal value of the sovereign was one pound or twenty shillings, it contained £2-18 shillings of gold but sold on the continental markets from between £4 and £10.

This situation was to be exploited by a number of counterfeiters in the late 1940’s and the 1950’s. They used gold in their fake coins but were still able to make a handsome profit. In 1952 the alarm bells started to ring loudly in the British Treasury and the Royal Mint when the Swiss Federal Appeal Court refused to extradite two sovereign counterfeiters to Italy. One of these counterfeiters was a certain José Beraha Zdravko, founder of one of the main counterfeit factories in Milan. The Swiss courts ruled that the sovereign could no longer be classed as money as it was not used as such in Britain.

A meeting of British government officials decided to authorise the Treasury Solicitor to take an active part in reversing this legal decision. Publicly the reasons for this were to protect the Royal Mint’s and the country’s prestige and commercial interests. In a confidential letter, S.Goldman from the Treasury appears to have stated the main motive in trying to prevent the counterfeiting of the sovereign:

Unfortunately we are not in a position to make public use of the argument that the copying of sovereigns may prevent us from employing them in our own semi-clandestine activities in the Middle East.

Ralph Anderson then took the lead in attempting to prevent this trade in counterfeit sovereigns. He brought professionalism and some would say a remarkable uncivil servant like energy to the task. He worked through British Embassies, their local legal advisors and with the prosecuting authorities. By July 1954 he was able to report that there were counterfeit sovereign cases before the courts in Milan (2), Turin, Coma, Trieste, Tangiers and Switzerland (3). By the end of that year the cases in Tangiers, Rome and Zurich had been successful. The Zurich case was crucial but taken by a canton level court and did not overturn the previous Swiss Federal Appeal Court ruling. There was one serious set back during the year when an Australian Court acquitted a defendant of counterfeiting sovereigns because they were not current coin. However the Australian government reacted quickly and the loophole in their law was changed by 1956.

The reverse of a 1918 counterfeit sovereign found in the USA

There were initially two main centres used for making counterfeit sovereigns, Milan and Syria. The coins from Milan were mainly imported into Switzerland and then sent all around the world. Most were sent to Beirut for the Middle East market. Anderson after a visit in January 1956 said, Beirut is the Clapham Junction in the movement of gold in and out of the Near East. The Saudi Arabian Finance Ministry reputedly bought 50,000 of these coins directly from a group of Swiss based traffickers. These Italian counterfeits also went to South America, Western Europe and Greece. The Syrian counterfeits were used mainly in the Middle East or smuggled into India.

The Italian counterfeits were considered to be of a better quality than the Syrian coins. It was suspected by the British authorities that the so-called Swiss counterfeits were merely the best examples of the Italian coins that had been trafficked through Switzerland. During this time the Royal Mint assayed a large number of the counterfeits. The Italian coins, probably mainly from Beraha’s organisation, were found to usually contain between 91.2 to 91.7% gold whereas the Syrian/Lebanese coins, attributed to Chatile and others, varied between 88.0 to 91.5% gold. Genuine sovereigns always contain between 91.6 and 91.7% gold. Beraha was to later boast (Note 1) that he used more gold in his coins than the Royal Mint. The Royal Mint’s assays proved this boast to be as untrustworthy as his sovereigns.

It is difficult to quantify the scale of the problem with any certainty but it is probable that the number of counterfeits was vast. The Treasury estimated that there were up to 300 million sovereigns in circulation in the world in 1955. The Milan counterfeit factory operated by Beraha was one of the first to be closed by the Italian police. It was estimated to be able to produce up to a thousand coins a day. The Swiss police stated that between December 1952 and April 1954 one group of traffickers brought over 400,000 counterfeits into Switzerland from Milan. Again in 1955 Anderson noted an estimate that there was anything between one hundred thousand and a million Italian counterfeits in the 15 to 20 million sovereigns in Greece.

By 1956 the British felt their actions were having a significant impression on the manufacture of counterfeit sovereigns. However they were concerned that the legal position was still very precarious. A number of legal appeals were still underway and an adverse decision in any one of these would have reversed the advances made since 1952. After a review of the situation it was decided to add another line of attack to help solve the problem. This was to increase the supply of genuine sovereigns. In 1957 the Royal Mint made over two million, new currency sovereigns. It then made currency sovereigns annually, except for 1960 and 1961, up to and including 1968. This produced over 45 million new coins. These coins were not available inside Britain but kept in the Bank of England reserves and available to meet demand worldwide.

The increased availability of genuine sovereigns significantly reduced the price of the coin compared with the value of the gold it contained. The increase in supply was probably helped by a slow reduction in demand. C.M.Pirie of the British Legation in The Yemen observed, There seems to be at the present time a far greater trade in American dollars. This led Anderson to state in a letter in 1959, In my opinion, …counterfeiting in Europe has been substantially stopped but there are indications of renewed counterfeiting in Syria.

The reduction in the price of a sovereign over its gold price removed the profit to be made from counterfeiting sovereigns using a twenty-two carat (91.67%) gold alloy. The reports on the Syrian counterfeits claimed they contained significantly lower amounts of gold, 40 to 60% and compensated by being thicker than genuine coins. This, use of less gold than the genuine coin, generated the manufacturers profit. The moneychangers in the Middle East because of the counterfeits inferior quality easily identified these coins. In consequence they were bought and sold for a lower price.

From 1960 to 1970 the numbers of counterfeits made never again reach the levels of the early 1950’s. There was counterfeiting in Beirut in the 1970’s of collector gold coins and probably currency coins. The devastation of Beirut in the 1980s seems to have stopped production of these coins. The large-scale manufacture of these counterfeits does not appear to have resumed after this time, however there are still a number of the older fakes in circulation contaminating the sovereign stock. This is especially true in the Middle East.

A small sidelight on this whole issue was shown during the first Gulf War in 1991. British Special Forces were issued with packs containing a number of sovereigns to buy assistance from local people behind enemy lines. The Ministry of Defence bought these coins in the Middle East. It is perhaps not surprising that when these were examined after the end of the conflict a number were found to be counterfeit!

The reverse of a 1913 counterfeit sovereign found in the sovereigns used by British Special Forces in the Gulf War

References

The main sources for this article are Royal Mint files deposited at the National Archive: MINT20-2317, 20-2318, 20-2319, 20-2320, 20-2321. These are titled, Counterfeit: sovereigns, and cover the period 1950 to 1959.

Note 1: Bloom, Murray Teigh, Money of their own: The Great Counterfeiters, London edition, Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1957.

Copyright Robert Matthews 2004